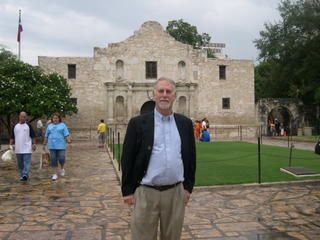

Memories of another era cried out to me as I strolled through hallowed ruins of the Alamo today. But Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie and company can rest in peace.

The Alamo is much more than a tourist destination or restored pile of adobe bricks to Texans. The small sign out front says it all in the subtitle: The Shrine to Texas Liberty.

Gentlemen are asked to remove their hats. Ungentlemen are watched like hawks by the guards. And hushed voices are the order of the day. Someone once told me that every Texan has two home towns, where they live and San Antonio. And every good Texan pays homage to the Alamo.

It doesn't matter that Bowie was a notorious slaver and some researchers think Crockett surrendered. It doesn't matter that the major battles of the Texas Revolution were fought elsewhere. And it certainly doesn't matter that the United Sates refused to let Texas into its club for years after the fight.

This is the Alamo. And folks in these parts Remember the Alamo.

But as I revisited the old Mission and bought a special trinket at the gift store, what I remembered was a very blond tyke. Back in 1989 he was my special little man who rode on my shoulders and looked at me with with piercing eyes that one minute shone blue and another seemed green.

I remember oh so well that summer when I had the chance to really be a dad. I had quit my newspaper job in Idaho that summer of 1988 and was waiting to enter graduate school at the University of Texas that fall. Cecile was putting in long hours in her new management job. And I got to spend each day, every day with Gillian and Garrett.

Gillian was always full of ideas for crafts or outings or movies or whatever. She was a typical active grade schooler. But Garrett was a preschooler with narrower ambitions. His favorite videatape by far was the story of Davey Crockett. And when I asked what he wanted to do for the day his reply was always the same: "Go to the Alamo."

I didn't mind. I loved walking on the stones of Alamo Plaza or soaking up the shade of the trees surrounding the shrine. But I couldn't put Garrett off long. We would reverently go inside the Alamo and walk up to the glass case holding Crockett's gun.

I didn't mind. I loved walking on the stones of Alamo Plaza or soaking up the shade of the trees surrounding the shrine. But I couldn't put Garrett off long. We would reverently go inside the Alamo and walk up to the glass case holding Crockett's gun.I once tried to tell him that that particular gun wasn't really "Old Betsy," and how unlikely it would be that even the Mexican Army would keep the gun of the defeated Texians.

Waste of breath. We were there to see Old Betsy. Again.

We made the pilgrimage many times that summer and each time I marveled as Garrett's eyes grew wide when he pulled his chin up to the glass case. It was a look of utter awe and admiration that any real hero -- or real father -- would give his life to receive.

So, yes. I remember the Alamo.